Nearly two weeks ago now, the lawyer for Russian cross-country skier Alexander Legkov published the decision a panel at the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) had come to after a hearing in May.

Legkov has been suspended by the International Ski Federation (FIS) since December, 2016, because of his presence in the McLaren Report, an investigation commissioned by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to assess potential state-sponsored doping by Russia at the 2014 Olympics in Sochi. Legkov won a gold medal in the 50-kilometer freestyle in Sochi, and is mentioned in multiple places in the McLaren Report’s evidence packet.

As we summarized last week, CAS agreed that it was justified for FIS to provisionally suspend Legkov pending further investigations into whether he committed a Anti-Doping Rule Violation (ADRV).

However, CAS decided that this provisional suspension could not be infinite and gave it an Oct. 31, 2017, deadline. After that point, FIS must either bring a full ADRV case against Legkov, or drop the provisional suspension until they have new information.

Besides the new deadline, there were a number of interesting details in the 51-page decision from CAS.

Before diving into them, the background: the IOC and FIS are considering a specific ADRV for Legkov: “tampering or attempted tampering with any part of the Doping Control”, outlined in the IOC Anti-Doping Rules for Sochi.

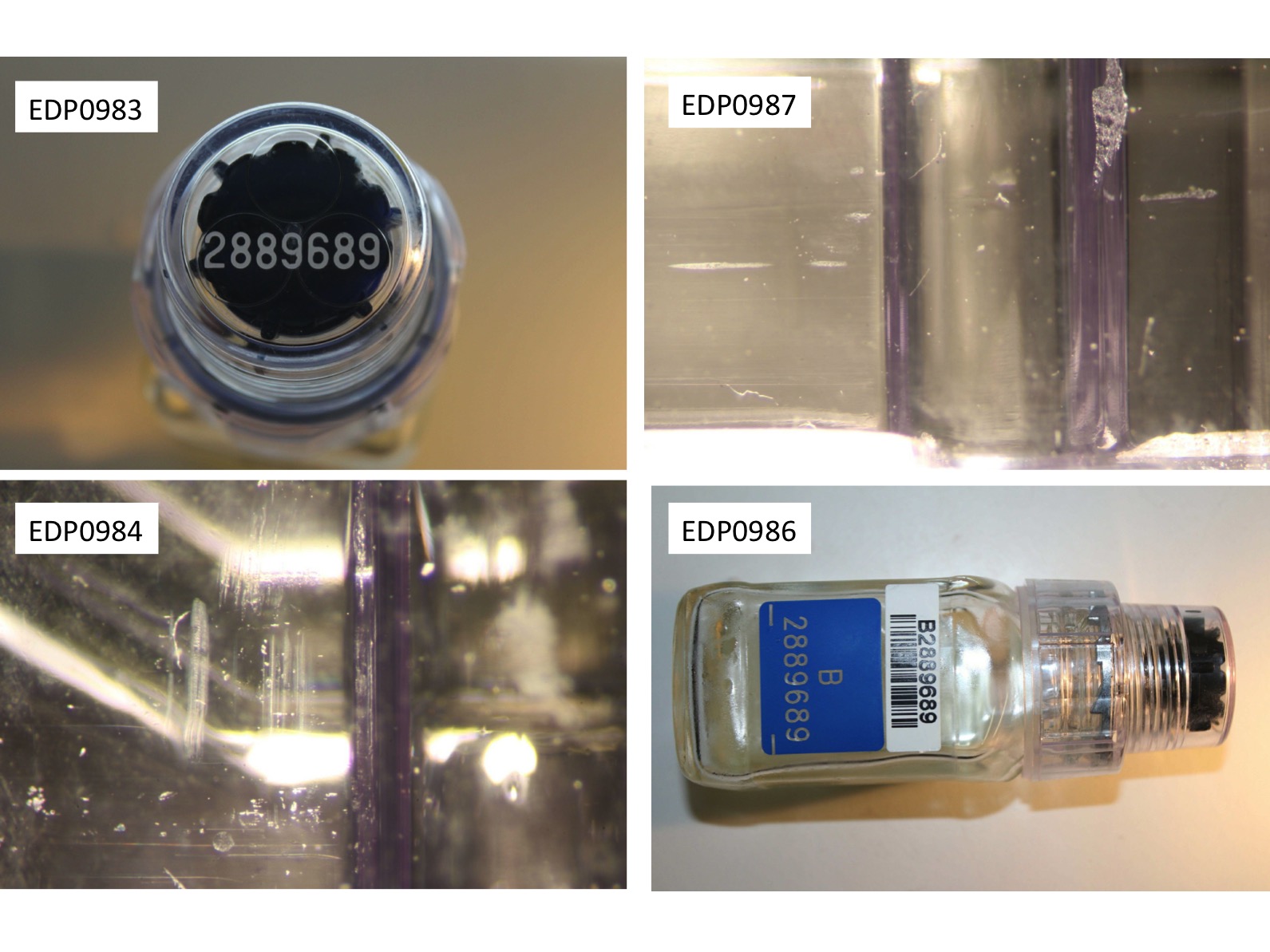

That’s because one of Legkov’s urine sample bottles showed suspicious marks when examined by a forensic expert in the McLaren Report. The conclusion was that the bottle must have been opened after the sample had already been collected, presumably in order to swap out a “dirty” urine sample for a “clean” one. This was the scheme outlined by the McLaren Report as well as news outlets such as The New York Times, whereby the Russians systematically cheated the anti-doping system.

Thus, the case hinges not on one doping sample: a urine sample collected on Feb. 23, 2014, the day Legkov won the 50 k.

- Provisional Suspensions Don’t Have the Same Standard as Final Decisions

The suspension that Legkov was appealing was a provisional suspension, not a final one. FIS is still considering whether and how to bring a doping violation case against him, at which point there will be a different set of hearings and, if he’s found guilty, the implementation of a ban. (The long delay is because FIS is waiting on evidence from another IOC panel in order to bring their case.) In that case, the standard suspension for a first-time doping offense is four years; as of today, Legkov has been provisionally suspended for nearly 10 months.

FIS outlined in their pleadings why it is important to keep suspected dopers out of competition while their cases are investigated:

“Maintaining the suspension mitigates the ‘serious further risk’ of requiring retroactive disqualification of the Athlete (should he be found guilty of an ADRV),” the CAS Panel wrote in summarizing FIS’s position. “The potential need to revisit rankings, re-distribute medals, or otherwise modify competition results would ‘diminish the value’ of competition for participants, sponsors, and the viewing public.”

CAS did not have a problem with this system, writing that “the provisional suspension occupies a space in which an ADRV is asserted, but not yet proven.” This is important, as it is likely to be used more and more frequently as the types of doping cases being tried gets more diverse.

When there is a positive drug test, things often move forward fairly quickly. A mandatory provisional suspension is automatically triggered with a positive “A” sample (once it is established that the athlete does not have a Therapeutic Use Exemption for the substance), and there’s not much debate as to whether this is justified or not. From there it is on to analyzing the “B” sample and having hearings.

But in non-traditional cases, which are becoming more and more common, provisional suspensions might play a bigger role – and putting them into place will have more gray areas. This includes cases like autologous blood doping, where athletes extract some of their blood, save it for later, and then re-infuse is to get a boost of red blood cells and oxygen-carrying capacity. There are (at the moment) few good chemical markers of this type of blood doping and all evidence must be observed directly.

Other cases, too, sometimes rely on direct observation of doping, police finding doping materials, or paper or electronic files indicating wrongdoing, even in the absence of a positive doping test. The four-year ban of Austrian cross-country skier Harald Wurm is one example.

Because provisional suspensions are intended to keep athletes out of competition while their cases are being fully investigated, the standard of proof required to implement and maintain a provisional suspension is less stringent than it is for an actual doping violation. By definition, evidence is still being gathered.

In American civil law, the approximate analogy is to the situation in which someone seeks a temporary restraining order to protect themselves from a partner whom they fear will cause them domestic violence. The standard of proof that must be met to receive such an order is one of the lowest standards used in American law, because it is important to act quickly in this situation and because a longer follow-up hearing will be held soon after at which more evidence can be developed.

Thus, merely having doubts about the evidence is not enough to overturn such a suspension: “In this appeal, a provisional decision is overturned if it has ‘no reasonable prospect of being upheld,’” the Panel wrote.

So: a provisional suspension can be put in place if there is a “reasonable possibility” of a doping violation existing, and can only be overturned if there is “no reasonable prospect” of a doping violation being proven.

In CAS’s view, FIS was justified in putting the provisional suspension into place last December. And secondly, CAS did not think that Legkov had proved that there was ‘no reasonable prospect’ of further developing their case, so the provisional suspension was upheld, albeit with a deadline.

- CAS Generally Trusts McLaren and Rodchenkov, With Caveats

Legkov and his legal team argued that the McLaren Report was riddled with errors and that it was never meant to establish the guilt of specific athletes anyway, only to investigate the mechanism of systematic doping. As such, he argued, the report shouldn’t be weighed too heavily in proceedings.

Likewise, the team painted Dr. Grigory Rodchenkov, the biggest whistleblower in the Russian doping scandal and a major source for McLaren’s report, as an unreliable source.

Quite separately from Legkov, the Russian government has also been seeking to discredit Rodchenkov. Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev called him “scum”, his assets were seized, and there’s currently a warrant out for his arrest.

While agreeing that the evidence in the McLaren Report was not enough to prove a doping violation, CAS signaled that in general it trusted the evidence and that it certainly shouldn’t be ignored completely.

“It would however follow from the report’s findings as to the corruption of an entire system, devised to favor selected athletes, that some individual athletes must have benefited,” CAS wrote of the argument that the McLaren Report was not intended to identify individual athletes for disciplinary measures. “It could not sensibly be concluded that whereas the system was corrupt in the manner identified nonetheless no athlete drew advantage.”

The one exception: emails that Rodchenkov shared with McLaren. The emails are fascinating, but CAS wrote that they were “without context” and therefore very difficult to rely on as indicators of anything in particular.

On Rodchenkov, too, CAS indicated that they value the testimony of whistleblowers, even and especially if those individuals have broken the rules in the past.

“Although the Appellant has strongly challenged the credibility of Dr. Rodchenkov, the Panel observes first of all that the testimony of persons guilty of wrongdoing themselves can be decisive in establishing the guilt of others, and that the extent of their own culpability may even add to their value, since it is likely to be the result of their extensive involvement, at high levels, in the unlawfulness being examined,” the decision said.

Relatedly, CAS recently used evidence from the McLaren Report to uphold the ban of a Russian triple jumper. According to documents in the evidence packet, she had participated in a “washout” scheme where she took performance-enhancing drugs at home in Russia, where positive tests were suppressed, and then traveled to international competitions once the drugs were undetectable.

- McLaren Didn’t Show

All parties probably would have loved to ask Professor Richard McLaren, who assembled the McLaren Report, some questions. But they couldn’t. The Canadian was invited to the hearing but declined – CAS wrote that he “chose not to make himself available.”

“From its perspective, the Panel regrets Professor McLaren’s absence and unavailability for questioning,” they wrote. “In any event, neither the Appellant nor the Panel has been able to pose questions to the person under whose supervision and control the evidence that fundamentally informs the suspension under appeal was gathered and organized.”

McLaren did give FIS a sworn statement, but it was after the deadline had passed for the two legal teams to exchange evidence. So it was not permitted to be used in the proceedings.

McLaren’s absence would have had stronger implications than simply the panel’s disappointment were this an American criminal case. The United States Supreme Court has interpreted the Confrontation Clause of the U.S. Constitution as requiring that a criminal defendant be able to cross-examine (that is, to “confront”) a witness against him, and specifically that prior out-of-court statements by a now-unavailable witness may not be used against hi at tria. McLaren’s physical absence from this hearing, in a case based almost exclusively on evidence he had previously gathered (but that the parties had not previously had a chance to ask him about), would have sufficed to overturn a conviction obtained on this basis under American criminal law.

- ‘I Live in Europe’ Is Not Enough

One of Legkov’s main refrains through this whole ordeal has been that he was training outside of Russia for the time leading up to the 2014 Olympics, and so could not have participated in a state-sponsored doping program.

Indeed: Legkov and a few other athletes made their own training group based primarily in Davos, Switzerland, with a non-Russian coach and physiotherapist.

“To the extent that any opportunity might have existed to tamper, moreover, the Appellant considers it precluded by virtue of his geographical isolation from Russia,” the CAS Panel wrote in its summary of Legkov’s arguments. “The Appellant’s trainings have taken place outside of Russia since 2011, under the supervision of non-Russian coaches and personnel. Similarly, the Appellant has ‘used exclusively medical services in Davos,’ Switzerland (stemming from an apparent disappointment with Russian doctors following a bout of exercise-induced asthma in 2008).”

But at some other point in the hearings, Legkov seems to have made the argument that Russian officials could have taken urine provided during medical tests he occasionally had to undergo in Moscow, and swapped it out from his Sochi sample without his knowledge or consent. Legkov’s Instagram does show him spending at least some time in Russia at a few points in the last few years – as would be expected. It’s his home country.

Furthermore, with the Olympics being in Russia, Legkov was by nature back in Russia before the Games. This was the time period the CAS panel seized on in agreeing that yes, there was a “reasonable possibility” that he could have committed a doping violation.

“While Mr. Legkov’s geographical distance might complicate day-to-day participation in the ‘chain of distribution’ of performance-enhancing drugs prior to Sochi, it does little to quell the reasonable suspicion arising from his appearance on lists relating specifically to the Olympics.”

This is interesting because the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), the international governing body for track and field, suspended the Russian track federation after the first part of the McLaren Report came out. As a result, Russian athletes could not compete in international events. But the IAAF made exceptions for athletes who lived and trained outside of Russia and were assumed to be tested routinely by non-Russian doping agencies.

The difference may be that in that case, the IAAF was assessing athletes’ current status and trying to protect current competitions. They knew which athletes to track; further testing can be ordered, to the extent that the federation trusts an athlete is clean at, say, World Championships.

In this case, FIS is trying to adjudicate a case from years past, rather than prevent doping in the future.

- ‘I Passed Many Tests’ Is Not Enough, Especially Since the McLaren Report Says Tests Were Suppressed

Like many other doped and non-doped athletes before him, Legkov argued that he had passed so many doping tests that his reputation should help absolve him from suspicion.

CAS didn’t buy this argument, and indicated that Russian athletes may in fact have a much harder time using it in the future. The McLaren Report indicated that one of Russia’s strategies to get their doped athletes to competition was to simply alter test results in ADAMS, the international anti-doping results management database, from “positive” to “clean”.

As such, the database can’t be relied upon.

“The Panel considers it difficult to draw a conclusion from an athlete’s appearance or absence in ADAMS, given Professor McLaren’s indication that the Moscow Laboratory routinely manipulated and concealed test results,” the Panel wrote.

Legkov was tested at least once by Russian authorities between Jan. 1, 2014, and when he arrived in Sochi for the Olympics.

“The Appellant provided at least thirteen samples between 1 January 2014 and 5 February 2014, the date of his arrival in Sochi; at least twelve of these tested clean by laboratories outside of Russia and ‘without any chance’ to be manipulated,” CAS wrote in their summary of Legkov’s legal team’s arguments.

In an email to FasterSkier, Legkov’s lawyer Christof Wieschemann wrote that the one remaining test was collected by the Russian Anti-Doping Agency (RUSADA) in Switzerland, and analyzed in Moscow. However, the very next day FIS collected “a sample for blood, blood passport and urine, [and] analyzed in Cologne [Germany].”

(Note: a previous version of this story assumed that the RUSADA test had taken place in Russia. According to Wieschemann, that is incorrect.)

- ‘I Passed a Test Two Days Before’ Is Not Enough

Legkov provided three urine samples and one blood sample at the 2014 Olympics; only the last urine sample showed signs of tampering. He argued that since the other samples were clean, he could not have doped at the Olympics.

“During the Olympic Games themselves, the Appellant adds, three urine samples were submitted, including one sample on 21 February 2014, i.e., a mere two days before the urine sample which according to the IOC exhibited signs of tampering and which triggered the provisional suspension,” CAS wrote of Legkov’s argument. “The Appellant accordingly considers it ‘evident that he did not use the cocktail prior to or within the Olympic Games.’”

CAS found this, well, ridiculous, especially given that the “Duchess Cocktail” – the mixture of illicit drugs alleged to be given to top Russian athletes whose “dirty” urine samples were later swapped out for “clean” ones – quickly disappears from the body, becoming undetectable.

“Intermittent consumption aimed at exploiting the cocktail’s short wash-out periods is entirely possible and, potentially in the Appellant’s case, desirable (given strict controls he faced in Europe prior to his arrival in Sochi),” CAS wrote.

“It is hardly unusual for doped athletes to start and stop the consumption of performance-boosting substances abruptly, evading detection,” the panel continued. “Sufficient time (nine days) lapsed between the first and latter two samples for traces of the Duchess cocktail to dissipate; similarly, to the extent that the Appellant may have waited until shortly before his Gold medal-winning event to begin taking the cocktail, the two-day period separating his second (clean) and third (suspected) urine samples does not lift the cloud of suspicion established by this inclusion in the Duchess List and related documents.”

- What Was FIS Doing About the Other 40 Cases?

In its arguments, FIS repeatedly held up the McLaren Report as a reliable source of evidence.

Furthermore, the arguments indicated that FIS had been paying attention since the day the report dropped, Dec. 9, 2016.

“The IOC’s notification letter dated 22 December 2016 laid out compelling evidence [about Legkov] that had been known to the Federation since at least 9 December 2016,” the CAS panel wrote in summarizing FIS’s position. “The unprecedented scale of Professor McLaren’s allegations in combination with athlete-specific data in the EDP, FIS insists, required an immediate and resolute response.”

While FIS may have made a relatively fast response with regard to Legkov and five others, it appears to have not taken public action in other cases. From FasterSkier’s assessment of the Evidentiary Disclosure Package (EDP), there were 46 skiers who were mentioned in the McLaren Report. This represented 99 anti-doping samples. FasterSkier summarized all of them in a database and wrote about the cases.

To public knowledge, however, FIS only issued provisional suspensions to six athletes: Legkov, Maxim Vylegzhanin, Evgeny Belov, Alexei Petukhov, Julia Ivanova, and Evgenia Shapovalova.

These were the six who seemed to be under investigation by the IOC for doping in Sochi. To public knowledge, FIS has not issued any formal sanctions or charges based on any of the other, non-Olympic, evidence in the McLaren Report.

FIS did, however, allow Legkov to keep training with the Russian National Team as of Jan. 18, 2017, “an accomodation intended to allow him to maintain his competitiveness pending the resolution of his case.”

- Competing in Sport Is Not a Fundamental Right or Liberty

Legkov made the argument that his right to a fair trial was being infringed upon, because he was being suspended without any charge. His legal team called on Swiss law to overturn the FIS suspension; in the CAS summary, they wrote that Legkov alleged “the provisional suspension’s incompatibility with Swiss fundamental rights.”

CAS was not sympathetic, noting that the components of due process under Swiss law – “the Appellant’s right to understand, confront, and refute the evidence against him” – were being followed by the very fact that the hearing was taking place.

“The question under Swiss law, moreover, is not whether the Appellant enjoys certain protections but rather to which degree they find expression vis-à-vis competing notions of associational autonomy,” the Panel wrote. “An athlete subject to sanctions proceedings internal to an association does not ‘require protection in the same measure as, for example, the accused in a criminal proceeding’… CAS sanctions result in a period of ineligibility to compete and forfeiture of prizes, not deprivation of liberty.”

- Anti-Doping Rules Are Hard to Write

In determining the “reasonable possibility” standard for proof of a doping violation with regard to provisional suspensions, the CAS Panel waded through several provisions in the FIS Anti-Doping Rules.

They found unclear the order in which provisions were supposed to be considered, and found that some provisions might even be inconsistent with others. While the Panel eventually decided that there was a clear way around this problem, they were not complimentary of the FIS rules.

“Though both options [for interpreting the FIS Rules] have merit, ambiguous drafting frustrates attempts at a definitive interpretation of the FIS Rules’ intended order of precedence,” the Panel wrote at one point.

“A literal focus on the word ‘assertion’ may therefore prove elusive,” they wrote at another. “The drafters’ intent finds no expression in a uniform, literal construction of Articles 7.7 and 7.9.”

It is the second time in just over a year that FIS has been rebuked over clarity of rules, although the first was not fully the fault of the federation.

The case of Norwegian skier Martin Johnsrud Sundby hinged on how to interpret rules about how much salbutamol, an asthma medication, can be inhaled in a certain period of time – and whether a nebulizer counts as an inhaler.

The rule in question was the WADA Code – written by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), not FIS – but in this case, FIS was applying the rule and thus was party to the proceedings.

“The Panel considers that the Athlete genuinely misunderstood the meaning of the β2A Provision, and also itself considers that the β2A Provision could have been drafted more clearly in certain respects (an issue the Panel will return to when discussing the appropriate sanction),” CAS wrote in that decision.

The notion of an adjudicative body critiquing a legislative body for unclear statutory construction is not unusual. The solution is, ideally, for the relevant legislative body to clarify the relevant text in a future session. In the case of asthma medication, the 2018 WADA Prohibited List updated its text on β2-agonists.

It remains to be seen whether FIS (or WADA, the IOC, or other sporting federations which use the same or similar language in their rules) will respond to this portion of CAS’s Legkov decision in the same manner.

Chelsea Little

Chelsea Little is FasterSkier's Editor-At-Large. A former racer at Ford Sayre, Dartmouth College and the Craftsbury Green Racing Project, she is a PhD candidate in aquatic ecology in the @Altermatt_lab at Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology in Zurich, Switzerland. You can follow her on twitter @ChelskiLittle.